What could be the most touristy town of Shekhawati, Mandawa appears the most when googling Shekhawati, be it hotels to stay in or havelis to visit. But Mandawa wasn’t always like this; in fact it once used to be a nondescript village until it came under the rule of Nawal Singh. He laid the foundation of Mandawa as we see it today and invited rich merchants to settle in Mandawa. Some of the prominent trader families in Mandawa were the Dhandhanias, Harlalkas, Ladias, Chokhanis, Sonthalias, Sarafs and the Goenkas. In those days, Mandawa was the heart of trade in the region.

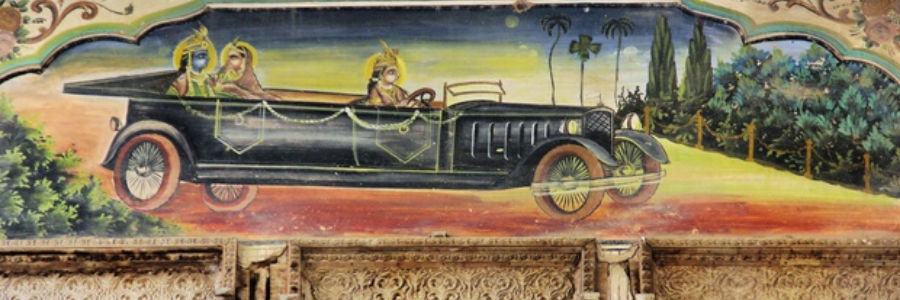

The grace is in colors used for the murals. Before the 19th century only natural colors like the lampblack and red and green and yellow ochers were used. Limes, indigo, vermillion, cow urine collected from cows fed on mango leaves was used for yellow, flowers and even silver and gold was used for colors. Around 1850s German colors hit the market and became popular with the artists and by the start of 1900s the English chemical colors had flooded the market.